Sign up here to receive The Yappie's weekly briefing on Asian American + Pacific Islander politics and support our work by making a donation.

Xu Lin, 38, knows his basketball.

Though he calls himself a Warriors fan, he has lived in Philadelphia ever since he immigrated to the United States from China at 16. He’s always rooted for the 76ers—they’re his home team.

But then the Sixers announced that they were planning to build a new stadium just a few blocks from Lin’s restaurant in Philadelphia’s Chinatown, a cultural hub for the city’s Asian American community and a neighborhood with a rich history that dates back to the 1870s.

“I feel like someone is stepping on our people,” he told The Yappie.

The basketball team, which is nearing the end of its lease at the Wells Fargo Center in South Philly, is planning its relocation with development group 76 Devcorp, led by Philadelphia-based real-estate mogul and recently minted Sixers co-owner David Adelman.

Design, demolition, and construction for the $1.3 billion project would take several years, with demolition projected for 2026 and construction beginning in 2028. The proposal estimates that the stadium would be ready for the 2031-2032 NBA season.

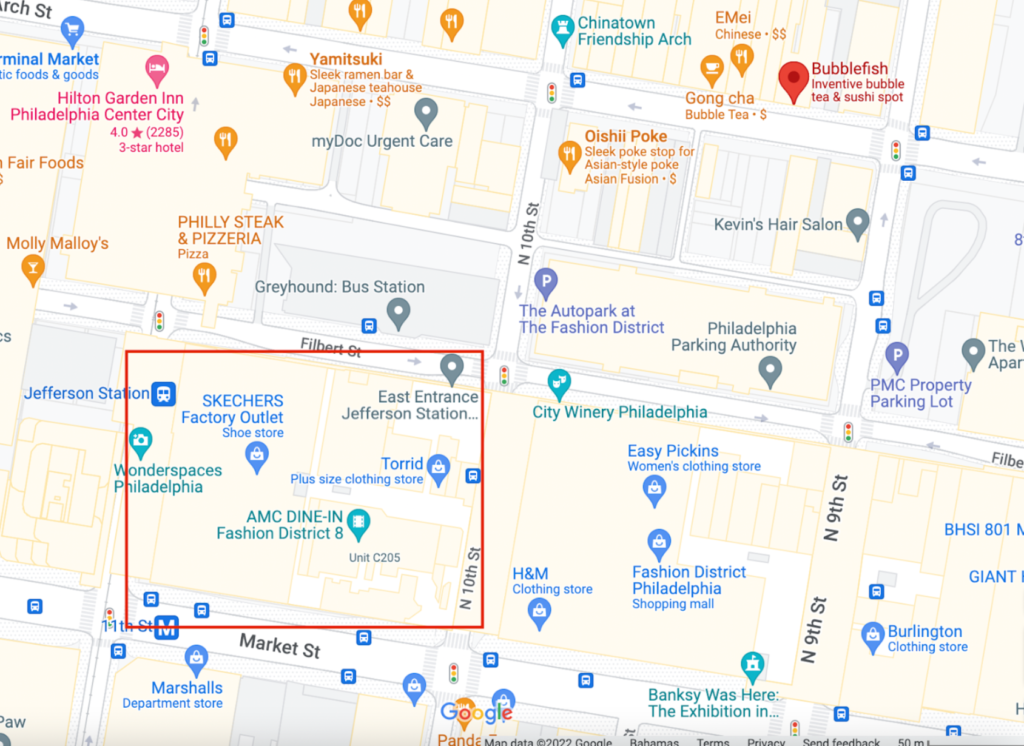

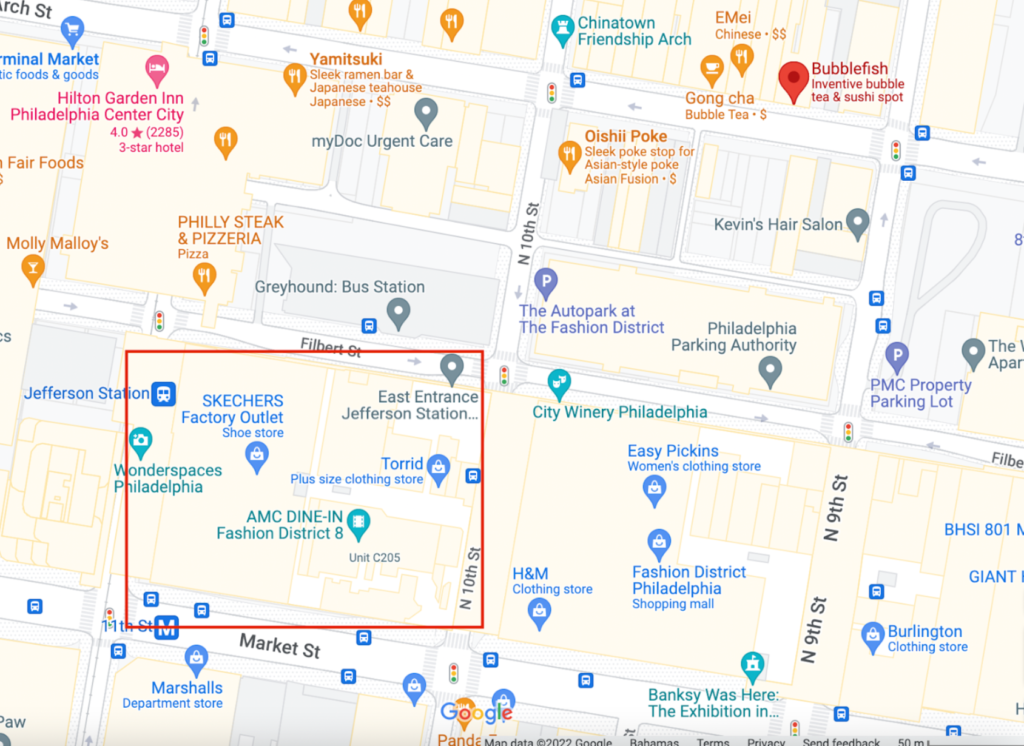

But the proposed arena would sit between 10th and 11th, along Market Street and bordering Chinatown—just two blocks from Bubblefish, the bubble tea and sushi restaurant Lin owns with his siblings.

“They are not really asking us for any input,” said Lin. “They are telling us they are coming.”

Safety, security, and the loss of a legacy

On Dec. 14, hundreds of people—mostly Asian Americans—gathered for a town hall-style meeting with a 76ers representative in Philadelphia’s Chinatown. Questions and remarks made in English were translated into Mandarin and Cantonese.

Hosted by Philadelphia-based advocacy group Asian Americans United (AAU), the meeting drew business owners, residents, elders, students, and children—all eager to raise their concerns publicly and directly for the first time.

Since the proposal was announced, community members have expressed concerns about potential impacts on traffic and parking, safety and security, as well as the local residents and businesses.

Debbie Wei, a founding member of AAU, said people are concerned about sports betting and “drunk sports fans during a time when Asians have been targeted for hate crimes.”

Developers, however, have said that building a new arena could bring more business to Chinatown and surrounding areas, including the nearby Fashion District which has struggled because of the pandemic. Plus, more sports arenas are moving to downtown locations.

“We want to be good corporate citizens,” David Gould, chief diversity and impact officer for the 76ers, told community members at the town hall. “We think that it could be good for the city as a whole.”

A worrisome future

Chinatown residents and business owners have fought previous attempts to construct large arenas in the neighborhood, including baseball and football stadiums as well as a casino.

Critics of the plan have pointed in particular to the changes in Washington, D.C.’s Chinatown since the construction of Capital One Arena, owned by Monumental Sports and Entertainment (MSE).

Opponents of the proposed Sixers stadium say that the D.C. arena has pushed out local business owners and residents over the past two decades.

“We saw what happened there. It’s a disaster,” said Lin, who visited the Chinatown area in D.C. with a group of people affiliated with Asian Americans United earlier this year.

“There’s no Chinatown anymore, not really,” he said.

Since the 20,000-seat arena opened in 1997, businesses have closed while new, corporate-owned restaurants have moved in.

Exit the Gallery Place-Chinatown Metro stop and you’ll find a Walgreens sign with Chinese lettering that translates to pharmacy—“藥房”—behind the iconic red-green Friendship Archway at H and 7th Streets. Walk around the block and you’ll pass a Chopt, a Smashburger, and a Chipotle—with name boards containing Chinese translations of the kind of food offered at each fast-casual chain.

The neighborhood’s Chinese resident population has been gutted, too. In 2010, about 3,000 Chinese residents lived in Chinatown. Now that number is fewer than 300, according to NPR’s D.C. affiliate WAMU.

In 2017, David Touhey, MSE’s then-president of venues, acknowledged that there were fewer Chinese restaurants in Chinatown since the arena’s opening.

“The restaurants that come into the area are what the people are desiring, and that’s why they get the high traffic,” Touhey told WAMU.

The Sixers did not respond to a request for comment regarding Chinatown locals’ concerns. But Gould, the Sixers’ representative, echoed Touhey’s rhetoric during the December town hall, noting that the arena would bring new business to once-thriving Chinatown.

Many locals remain doubtful, however.

“It’s going to destroy the community,” said Lin.

A familiar battle—and what Philadelphia stands to lose

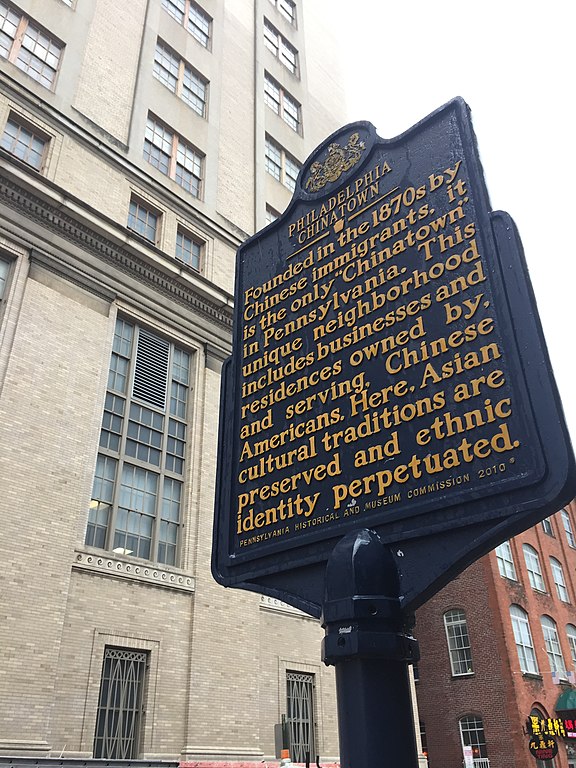

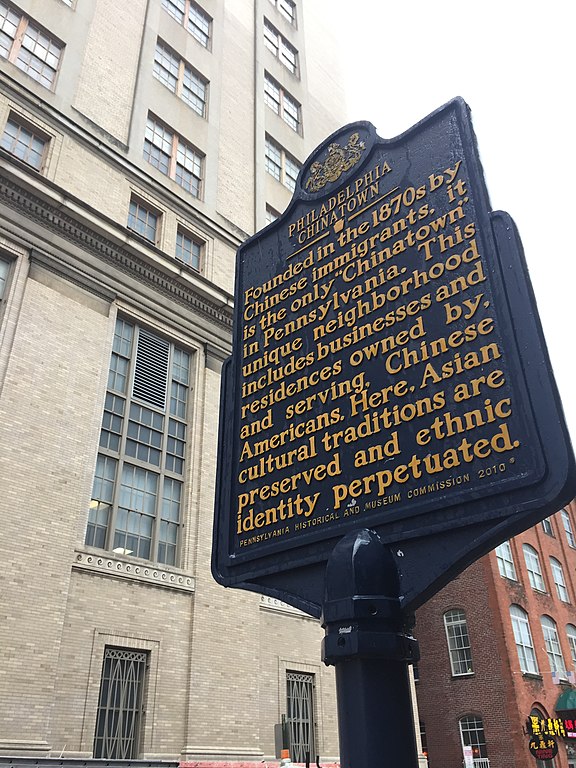

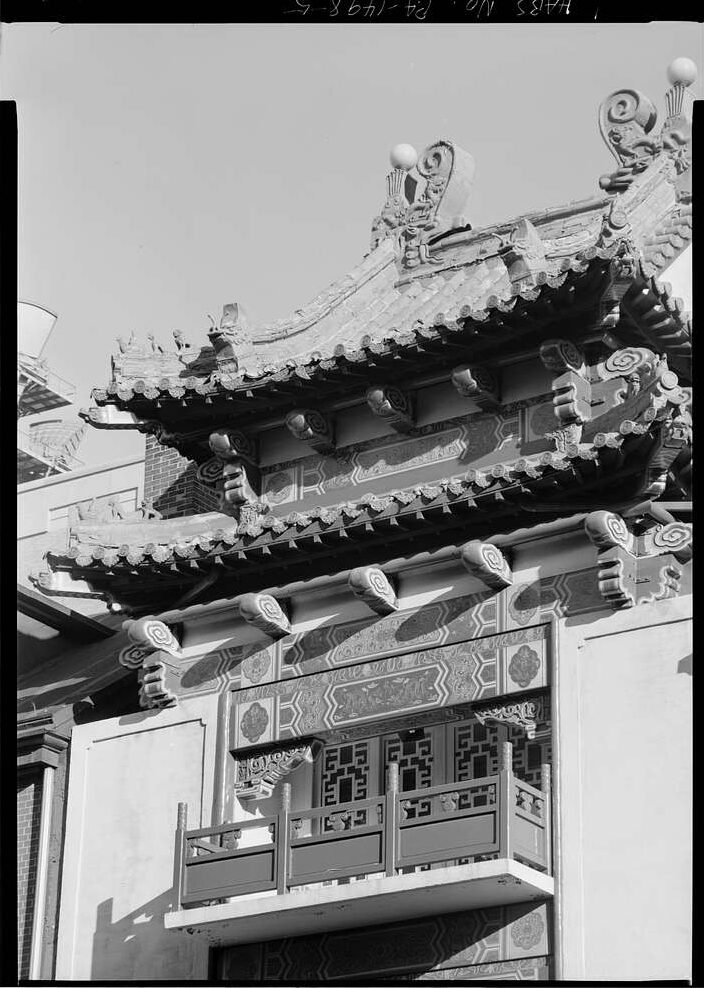

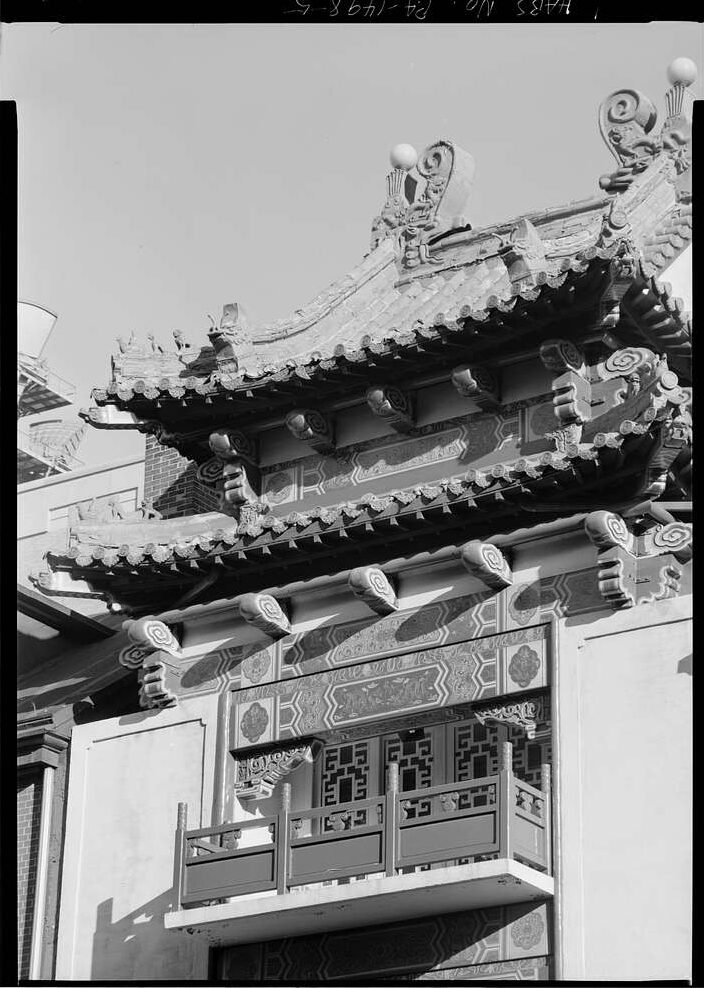

In the 1870s, a group of Chinese migrants driven out of the West settled around the 900 block of South Philadelphia’s Race Street, opening restaurants and laundromats and establishing the beginnings of a vibrant neighborhood that is now a cultural hub for immigrants across the East Asian and Southeast Asian diasporas.

Following the end of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, families and friends began to join the mostly Chinese men who’d now expanded their blocks of business, transforming the area into a culturally rich, family-centered community.

But in the late 1900s, as the city of Philadelphia began to upgrade its business districts and transit infrastructure, construction projects chipped away at Chinatown—which was ultimately cut in half by an expressway, the I-676.

Still, Chinatown community members and activists protested the destructive actions, leading the city to designate Chinatown a special district with limits on commercial and industrial activity in order to “protect the historic, cultural, aesthetic, residential and economic vitality” of the area.

Since then, residents have continued to fight corporate developers’ repeated attempts to break ground on Chinatown. In 2000, Chinatown leaders threatened to file a racial discrimination lawsuit against the city of Philadelphia if it allowed the Phillies baseball team to relocate to Chinatown, which the lead developer also insisted would spur business for stores in nearby shopping district Center City.

And in 2013, Chinatown residents protested plans for a casino, saying it would target the Asian community by increasing the risk of gambling addiction among local immigrants. (A 2019 study of residents in Boston’s Chinatown found that low-income immigrant workers, particularly refugees who fled war, were at the highest risk of developing gambling addictions.)

“I won’t let them destroy my community,” said Derek Sam, who owns Little Saigon Café, a Vietnamese restaurant that sits two blocks away from the site of the proposed arena. “That’s my home.”

Sam came to the United States 42 years ago as a refugee from Vietnam. His house in Chinatown is three blocks down from the would-be arena.

He said he first heard about the plans for the arena from ABC News and has remained frustrated with the limited information the Sixers have made available to Chinatown business owners.

He added that he thinks the developers underestimated the pushback they’d receive from the Chinese and Chinatown community, believing them to be quiet and quick to agree.

“But they’re wrong,” he told The Yappie. “We will do whatever we can to save Chinatown.”

Suspicions amid a lack of transparency

In early December, ahead of the town hall, a controversial clause in a routine Philadelphia City Council parking lot refinancing bill raised alarm bells among advocates who called it a subversive move by developers to fast-track the arena.

The clause would have allowed the city to close down a block in Chinatown—the same location proposed for the Sixers’ arena. Advocates suspected that the clause was added to the bill on the developers’ behalf.

“Any legislation will not be considered unless shared with the Chinatown community,” councilmember Mark Squilla, the author of the bill, told community members at the Dec. 14 town hall.

Ahead of a Dec. 7 council meeting, a lawyer working with the Sixers’ development team had emailed Squilla a revised version of the bill that included the clause, The Philadelphia Inquirer reports.

But Squilla told the Inquirer he was not aware of the updated wording and asked the mayor’s office to remove the clause from the bill after community members voiced their concerns against it.

Philadelphia’s city council ultimately passed the bill without the controversial clause.

“The people of Chinatown are not anti-development,” said Mohan Seshadri, executive director of the Asian Pacific Islander Political Alliance, an organization serving AAPIs in Pennsylvania. “They’re anti-development that is not accountable to them.”

Some Chinatown business and cultural leaders have formed a group called the Chinatown Steering Committee to meet with Sixers representatives and evaluate the stadium’s impact on the area.

But many community members say that the steering committee, set up by the nonprofit Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation, does not represent their interests. PCDC Executive Director John Chin did not respond to two requests for comment.

Up until the meeting, there’d also been a lack of in-language communication from the developers, Seshadri said. Many community members say the Sixers’ team has kept them in the dark.

“When we talk to the community in the streets and in places of worship and in restaurants, we hear fear and we hear anger,” said Seshadri.

Growing up in Philadelphia, Lin would often hang out with his friends in Chinatown after school. “They are very sad,” he said of his friends. “They want to come out and support.”

But Lin told his friends to hang tight—at least for the first town hall. There would be more opportunities for them to participate in the fight against the Sixers down the road.

“We will fight with everything we have,” said Lin.

At the meeting, community members stood up one after the other to raise their concerns as a microphone was passed around and remarks were translated into Mandarin.

“Save our Chinatown!” they chanted.

The Yappie is your must-read briefing on AAPI power, politics, and influence, fiscally sponsored by the Asian American Journalists Association. Make a donation, subscribe, and follow us on Twitter (@theyappie). Send tips and feedback to [email protected].