Sign up here to receive The Yappie's weekly briefing on Asian American + Pacific Islander politics and support our work by making a donation.

When Bella Collins’ older brother Angelo Quinto was experiencing an episode of paranoia, she called the police, hoping they would help de-escalate the situation. When the police arrived, they instead handcuffed him and laid a knee on his back.

Five minutes later, the Filipino American Navy veteran was unresponsive, a pool of blood on the floor. Three days later, he was pronounced dead.

What followed was tireless advocacy for change by Quinto’s family. Since his death in December 2020, Quinto’s family has helped push through a California bill banning police restraints that impair breathing, building a coalition of over 75 community organizations demanding “Justice for Angelo Quinto” along the way.

But accountability still hasn’t arrived, according to his family. An investigation by the Costa County Sheriff’s Department ruled the cause of death to be “excited delirium” rather than officer wrongdoing, a term denounced by medical associations and also used to defend police officers involved in the killings of George Floyd, Elijah McClain, and Daniel Prude.

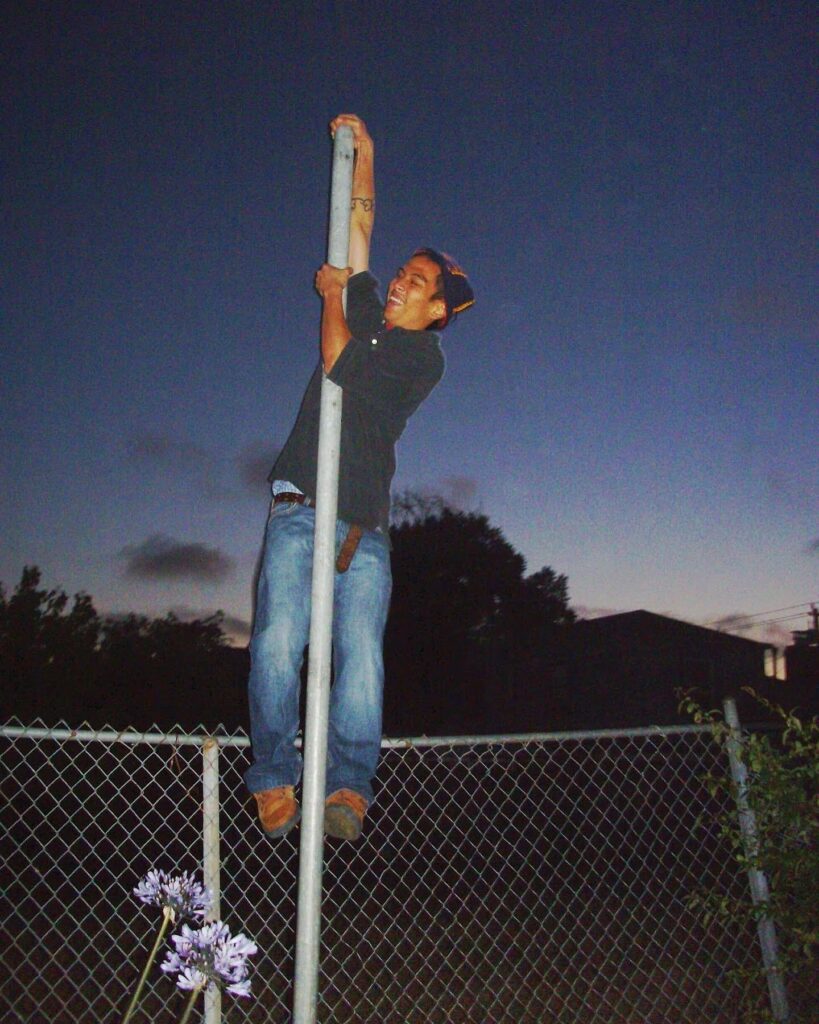

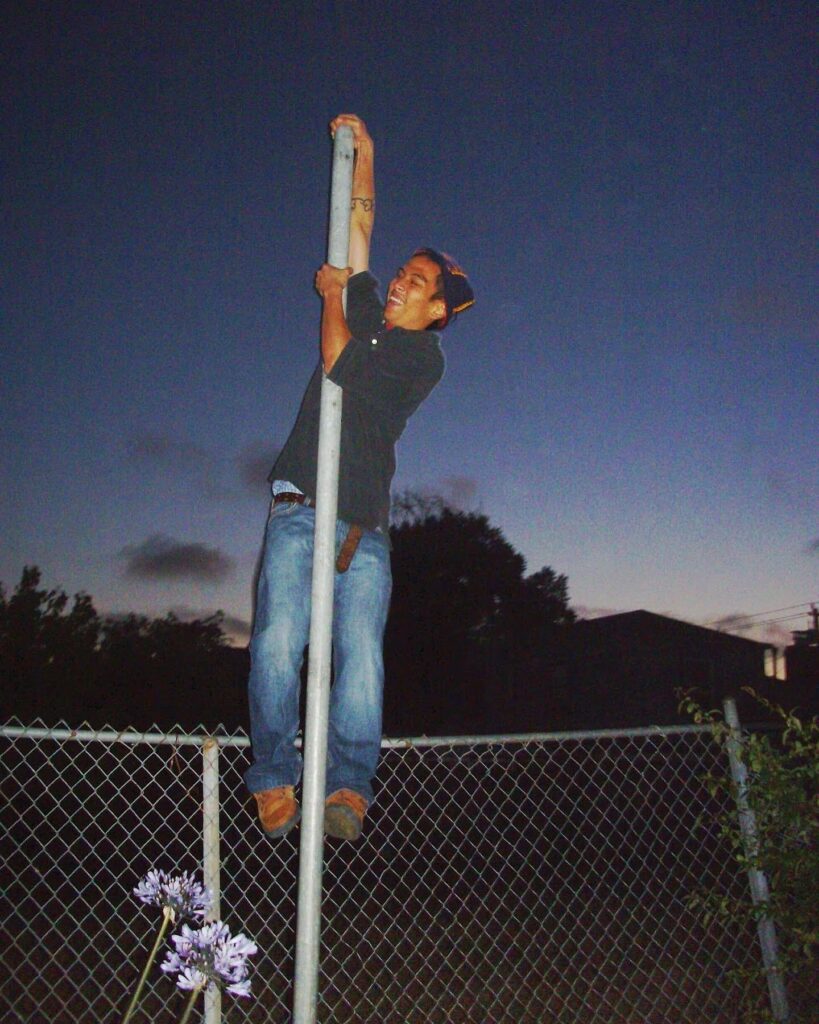

Last month, on the two-year anniversary of Quinto’s death, the family gathered with advocates and public officials to honor Quinto and continue calling for justice.

Police remain systemically protected from accountability for disproportionate violence against Black people and other people of color, two years after the police killing of Floyd and the “defund the police” movement. Protests reignited last month across the nation after five Memphis Police Department were captured on camera holding down Tyre Nichols, a Black 29-year-old man, while repeatedly beating, kicking, and pepper spraying him. Nichols died days later.

With the economy and abortion dominating the midterm elections, police reform appeared to take a backseat. But it hasn’t among Quinto’s family members—nor among AAPI advocates. AAPI activism like Quinto’s family’s fight for accountability, and other community-based, holistic solutions are necessary to keep all communities safe, civil rights advocates say.

Disproportionate police violence against people of color

Police killed non-Hispanic Black people at 3.5 times the rate of non-Hispanic white people from 1980 to 2019, according to a 2021 study published in the journal The Lancet. For Hispanic and non-Hispanic Indigenous people, the rate is around two times that for non-Hispanic white people.

Large-scale data on police violence against AAPIs is unavailable, but many AAPI groups— especially Southeast Asians, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders—face high rates of police violence, according to a 2022 report published by the AAPI Civic Engagement Fund.

In Oakland, Samoans have the highest arrest rate in the city, and across California Asian juveniles were more than twice as likely to be tried as adults compared to white juveniles, the Southeast Asian Resource Action Center noted in a 2015 report.

In 2019, 35% of the Honolulu Police Department’s uses of force were against NHPIs, who make up only 10 percent of Hawai‘i’s population.

In December 2019, Minneapolis police officers shot and killed Hmong American Chiasher Vue, whose daughter said he had undiagnosed mental health issues, on the porch of his house. Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman declined to file charges.

In December 2020, Pennsylvania state police killed Christian Hall, a 19-year-old Chinese American who was standing still with his hands raised above his head when officers shot him.

In April 2021, Texas police officers killed Rescue Eram, a Micronesian citizen from Guam, on the side of an interstate highway.

Lack of accountability in a broken system

Police brutality is enabled by the fact that officers are systemically protected from accountability for their violence. More than a thousand people have been shot and killed by police in the last twelve months, according to the Washington Post’s police shootings database.

The legal doctrine of qualified immunity protects police from facing charges for killing someone if their actions are considered “objectively reasonable”—satisfied as long as an officer says they are in imminent fear of death or serious injury, even if that fear was based on a mistaken belief—and did not violate any “clearly established statutory or constitutional rights,” which also often fails to hold police accountable because there are rarely established precedents that exactly match a given case of excessive force.

And because prosecutors rely on police officers for their criminal cases, they often avoid prosecuting them for misconduct.

Antioch police didn’t publicly disclose Quinto’s death until probed by the San Jose Mercury News a month later and maintained that officers had not used force against Quinto.

While an independent examination commissioned by Quinto’s family concluded that he died due to asphyxiation from several minutes of being pinned down by police, the county’s coroner investigation attributed Quinto’s death to “excited delirium.”

The term was also used to defend police officers involved in the killings of George Floyd, Elijah McClain, and Daniel Prude, though it has been denounced by the American Medical Association, American Psychiatric Association, and Physicians for Human Rights as an unscientific diagnosis commonly used to escape accountability.

Records obtained by Quinto’s family lawyers also revealed that police had told paramedics he was high on methamphetamine—the independent autopsy did not find any drugs in Quinto’s system.

“What we saw was cover-up after cover-up,” Robert Collins, Quinto’s father, told The Yappie. “The police have gotten enough resources to protect themselves.”

“Adrenaline flowing through the system”

Despite renewed attention on police brutality, funding for militarized policing has grown while other community safety strategies and even de-escalation training have received fewer resources.

State and local governments spent $205 billion on police and corrections in 2019, but only $57 billion on housing and community development, according to the nonprofit thank tank Urban Institute. Through the Department of Defense’s 1033 Program, police have accessed over $6 billion of military equipment.

Meanwhile, a 2015 study by the Police Executive Forum found that new officers across 280 municipal, county and state law enforcement agencies received an average of 58 hours of firearm training but only eight hours of de-escalation training.

“There’s so much adrenaline flowing through the [police] system. It’s not about talking things down; it’s about arresting somebody and preventing something and shootings,” Collins said. “Angelo … was so dehumanized. He was quiet and … 100% compliant, and they took his life because of it.”

A May 2022 Gallup poll found that half of American adults supported “major changes” to policing, with 81% supporting changes to legal practices to hold police accountable for violence.

But while social media campaigns have pushed “the average citizen [to understand] that police abuse and killing were wrong and that police would need to be accountable,” polarization in the discourse has prevented more meaningful change.

Holistic, community-based solutions

Police brutality does not stem from a “few bad apples,” nor can it be solved by increasing representation of communities of color among police, advocates say.

“Organizations that are based in community … know best what the method is to reach lawmakers, policy makers, to engage communities, to tell the story, to be very clear about the policy that they want to have implemented,” she said. “It’s not one tactic or method; it’s a range.”

One Black and Southeast Asian community organization in Madison, Wisconsin—Freedom Inc.—has focused on police presence in local schools. Police presence leads to increased surveillance and criminalization of Black community members, past studies have found.

The organization engaged students in schools, hosting more than 50 events to push the Madison Metropolitan School District Board of Education to unanimously vote to terminate its contract with the Madison Police Department in 2020. The board voted against the measure only the previous year.

The Coalition of Asian American Leaders (CAAL) in Minnesota is also working with Black, Afro-Latino, Jewish, and labor organizations to prevent unforeseen immigration-related consequences by advocating for a post-conviction relief bill..

“We’re in alignment to say, ‘Hey prosecutors, judges, please be mindful when you’re making decisions,’” said CAAL Executive Director ThaoMee Xiong. “For a person being charged with a crime, is this the appropriate charge? When you’re asking them to plea out, will this plea impact their immigration status?”

The Quintos' legislative fight

For Quinto’s family, stories about the impact of police violence have been important vehicles for change.

It’s common within many Asian American communities to “be compliant and do nothing regardless of what is happening in front of you,” said Cassandra Quinto-Collins, Quinto’s mother.

Quinto’s story showed that police brutality isn’t limited to those who commit crimes, but rather can happen “to anybody in a weird situation when a lot of factors come together,” Collins said.

On Feb. 18, 2021, less than two months after Quinto’s death, the family announced at a press conference that they had filed a legal claim alleging wrongful death, assault, battery, and negligence against the city of Antioch. Soon after, more than 170 Filipino American organizations across the U.S. came together to form the Justice for Angelo Quinto, Justice for All coalition.

On Feb. 23, 2021, Quinto’s family and 300 other community members attended the Antioch City Council meeting and “kept them up past midnight” making demands for change, Robert Collins said. The demands were “naive,” Collins recalled, including requests for body camera footage that didn’t exist, but helped set the campaign in motion.

By March 10, 2021, the coalition had attracted the attention of then-California Assemblymember Rob Bonta (D), who spoke at a vigil on Quinto’s birthday. A few weeks later, Bonta introduced legislation to bar police from using holds that impair breathing. Months of community advocacy and legislative testimony by Quinto’s family members led to the bill’s passage and enactment in September 2021.

In September, Bonta—now California’s attorney general—launched an investigation into Quinto’s death.

Solidarity for sustained advocacy

Quinto’s story has faded from memory since two years ago, and its ability to drive change has faded with it, said Collins. A second bill that the coalition worked to introduce last January would have required the separation of sheriff and coroner’s offices to prevent internal cover-ups, but failed to pass the state Senate by the end of the legislative cycle.

For sustained change, “we need to get better about building the relationships and the bridges to other families, to other stories.”

The family’s initial press conference was attended by family members of other victims of police violence, including relatives of Oscar Grant, Miles Hall, and Richard Perez, who had been killed by officers of various Bay Area police departments.

In their claim and lawsuit, Quinto’s family is represented by John Burris, the civil rights lawyer who among other police violence cases represented Rodney King against the Los Angeles Police Department.

Solidarity and organizing across racial lines must happen in order to stem police violence and overhaul the current system protecting officers who kill in the line of duty, AAPI advocates say—a need that has only grown as the surge in anti-Asian hate led to divisions and finger-pointing.

Many Asian Americans have been pushed away from supporting police reform due to the false narrative that perpetrators of anti-Asian violence are predominantly Black people when the vast majority are actually white. This belief defocuses “attention from police violence against Black people and [refocuses] it instead on police as critical partners, saviors, and protectors of the AAPI community,” the report notes.

Proponents of holistic reform have also run up against community leaders who have advocated for an increased police presence to prevent anti-Asian violence, especially those speaking for business owners and older community members. Long-term support programs won’t protect Asian Americans from crime now or in the near future, they say.

But Xiong emphasized the importance of solidarity while strengthening public safety, and that over-policing and mass incarceration ultimately hurt AAPI communities, especially in urban areas like Minneapolis where communities of color are often concentrated in the same areas.

“If our Asian American communities are not safe, then our African American communities are not safe. And the reverse is true—if our African American communities are under attack, it also means our Asian American communities are under attack,” said Xiong.

Awareness of this connectedness and engagement with police reform is necessary for the well-being of AAPI communities, the AAPI Civic Engagement report emphasizes. “What stake do AAPIs have in participating in the national conversation led by Black voices and the BLM movement? In short, our lives and the possibility of a just society depend on it.”

The Yappie is your must-read briefing on AAPI power, politics, and influence, fiscally sponsored by the Asian American Journalists Association. Make a donation, subscribe, and follow us on Twitter (@theyappie). Send tips and feedback to [email protected].