EDITOR'S NOTE

Welcome to the ninth installment of The Yappie’s series featuring Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) newsmakers, rising candidates, and lawmakers. This story was originally published by Mochi Magazine. If you’re interested in being featured, please email [email protected].

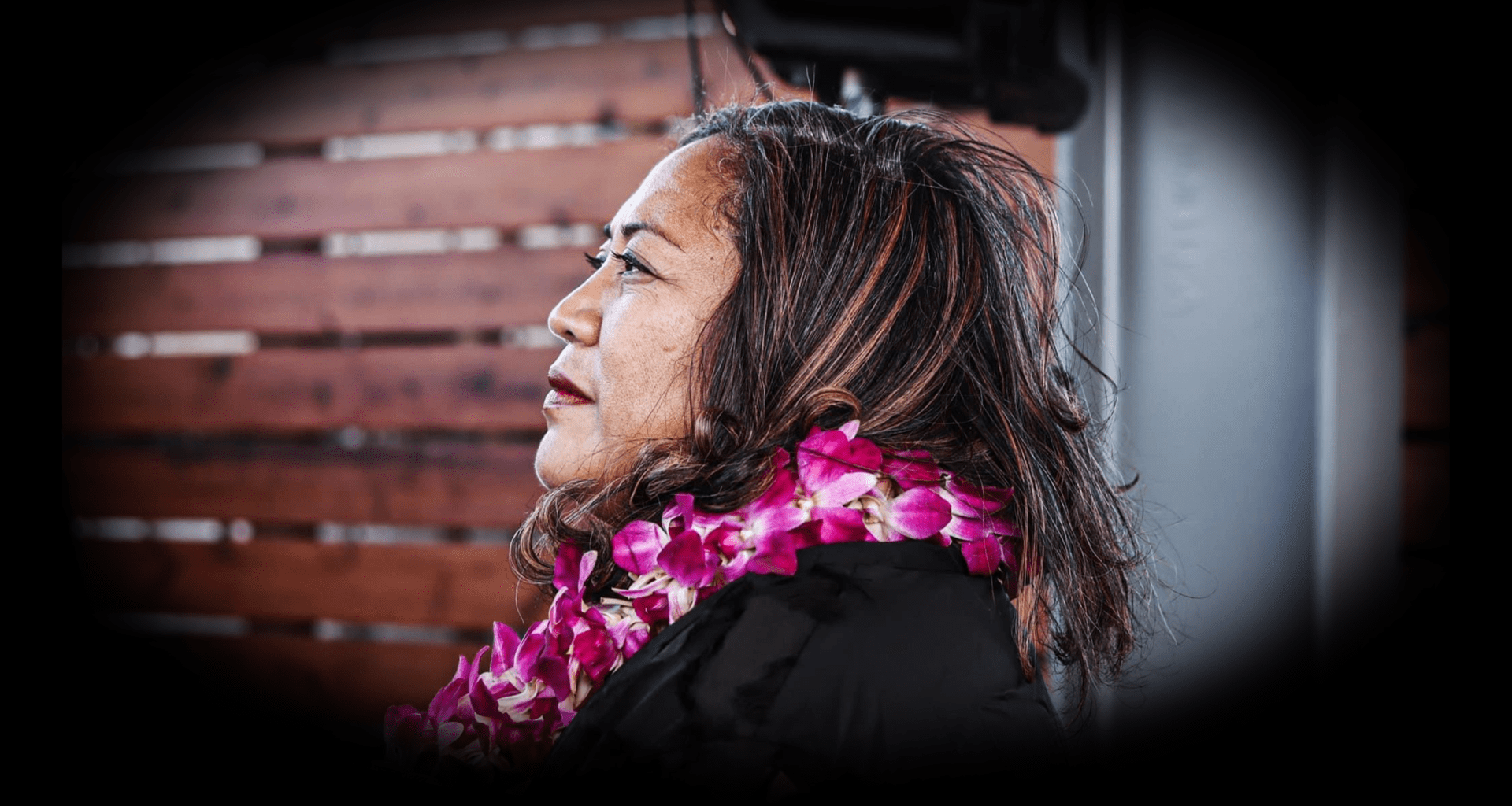

When Manufou Liaiga-Anoa’i was chosen as vice president of the Daly City school board, she was honored. Her family and community gathered to celebrate her achievement at City Hall, but then “a veteran board member literally lost her mind,” Liaiga-Anoa’i told Mochi Magazine. A colleague felt that she “deserved” the role more, she said.

So what did Liaiga-Anoa’i do? She withdrew and even nominated that particular board member for the position of vice president.

“That’s my culture,” she says, “Servant leadership in my Pacific Islander community is just an innate behavior and practice—and a value I embrace.”

That ruffled some feathers because Liaiga-Anoa’i was the board’s desired nominee. But this brand of humility is simply a part of who she is—so much so that the following year the same exact scenario played out again. When asked why she conceded twice, Liaiga-Anoa’i responded, “I don’t need a title to facilitate the work.”

Manufou Liaiga-Anoa’i—simply “Fou” to friends and family—is a first-generation Samoan American activist running for city council in Daly City, California, a town with a population of just over 100,000 directly south of San Francisco. If she wins, she will be the first Pacific Islander in the state of California to sit on a city council, according to Liaiga-Anoa’i.

But being the first or only Pacific Islander in these spaces is not new to Liaiga-Anoa’i. She was the first Pacific Islander to serve on the San Mateo County Commission on the Status of Women and the first Pacific Islander to take on a number of positions over her 35 years of advocacy and servant leadership. While titles may not matter to her, Liaiga-Anoa’i says she understands the importance of taking up and occupying space in order to represent and elevate her community as well as other marginalized groups.

Though the busy mother of six was tapped several times to run for Daly City’s city council in the last decade, she ultimately deferred until this year because she didn’t feel she was done in her role on the school board.

Under her tenure, she connected communities of color—especially families raising and caring for children with disabilities—to San Mateo County services to fill the gaps between what is provided by the local school district, medical insurance, and other programs. Liaiga-Anoa’i is also passionate about investing in youth development, creating programs that support entrepreneurship and internships and growing a successful youth cinema project that is aligned with common core standards in education.

“You show up”

If elected to the Daly City City Council, Liaiga-Anoa’i would have multiple high priorities, she said. Chief among them is to build a level of civility and cohesion on the council. She notes that when she started on the school board seven years ago, people would comment on the toxicity and unproductive nature of the meetings. At times, the interactions would even get physical.

“I asked myself, ‘What am I walking into?’ But again, that's my culture—I feel like you show up. People recognize how you show up, and you model the behavior that you would like to see in that space,” explains Liaiga-Anoa’i.

That's my culture—I feel like you show up. People recognize how you show up, and you model the behavior that you would like to see in that space.

— Manufou Liaiga-Anoa’i

After she served on the Daly City school board for just a year, a member of the California School Board Association and her fellow school board members remarked that the environment and space had been more positive since Liaiga-Anoa’i joined.

“I don't want to take full credit for that,” says Liaiga-Anoa’i. “But I do know that if we're intentional and there's consistency, you can shift these behaviors and get people on board.”

Her ability to quell unrest might come from the fact that she is no stranger to community meetings. As a 7 year old, her mother Papali’i Manufou Fonoti Liaiga-Mulitauaopele would take her to meetings in order to translate English into Samoan and vice versa.

“She had to make many tough decisions and her faith was unwavering and her word had great value in our community—folks relied on her and she never failed them,” Liaiga-Anoa’i recollected in a prior spotlight on her life. “It was important to her that she always delivered and set a good example for other women to follow.

Liaiga-Anoa’i’s mother serves as an inspiration, she said. A bold advocate, board member for Samoa Mo Samoa, and member of many other Saoman organizations, Liaiga-Mulitauaopele balanced an active public life while raising her children as a divorcee and later widow in addition to sending money home as part of her duties as high chief of her community.

One time, her mother and a group of other Samoans headed to Sacramento with Liaiga-Anoa’i in tow. Their mission: to advocate that Samoans be included in government forms, such as the U.S. Census. This was typical of Liaiga-Mulitauaopele. Despite her limited English language proficiency, Liaiga-Mulitauaopele would walk into the offices of mayors without an appointment and demand to be seen on behalf of her people, all with a young Liaiga-Anoa’i by her side to translate.

Her mother would tell her, “Fou, all you have at the end of the day is your name, your word, so make sure it’s worth something.” Every day, Liaiga-Anoa’i follows in her mother’s footsteps, she said, aiming to listen to the needs of her communities and take action in partnership with allies.

Keeping tradition alive

A San Francisco native, Liaiga-Anoa’i appreciates that people can see themselves through her, not just as a Pacific Islander but as a woman of color from an immigrant community.

Her parents came to this country like many other AAPI immigrants in “search of the American dream.” As founding members of the first Samoan church in northern California, her parents kept the Samoan culture alive, a practice that Liaiga-Anoa’i continues with her own family and community.

A memory that Liaiga-Anoa’i shared in a previous interview was that her mother would store fortune cookie papers in an empty Pond’s jar. Every day, after saying a prayer together, Liaiga-Anoa’i was tasked with translating a fortune from the jar into Samoan for her family. It’s a ritual she continues today with her family, not only to promote the continuation of the Samoan language but also to spark a sense of purpose and hope.

Liaiga-Anoa’i also works to keep tradition and language alive for her community beyond her own household through Camp Unity, a summer enrichment program for Pacific Islander youth that she founded in 2011. Camp Unity, which has served over 8,000 children across the San Francisco Bay Area, gives participants six weeks to explore their creativity and culture through Polynesian performing arts, language classes, traditional music appreciation, and more.

A strong proponent for ethnic studies, Liaiga-Anoa’i has shared that ethnic studies is inclusion. “Ethnic studies affords us the opportunity to enhance awareness of the numerous contributions, struggles and all that we’ve been able to do in our vibrant communities. The positive influences of having one’s cultural traditions, language, and history magnified in our classrooms is truly transformative,” Liaiga-Anoa’i said.

Not only does Camp Unity showcase the wonders that being in touch with one’s own culture can do for youth, but it also has a 98% retention rate following students from K-12 and beyond—many stay in the program until they graduate high school and return to volunteer.

It also serves as a pipeline for educators of color. The all-volunteer staff reflects the population served, allowing for cultural congruence in educational spaces but also professional development for those looking to go into teaching.

Liaiga-Anoa’i is also the founder of the Polynesian Heritage Celebration and Awards, and the Miss Samoa Golden Gate Scholarship Pageant. She co-founded the San Mateo County Pacific Islander Democratic Club and Samoan Heritage Week in San Francisco, and coordinates and participates in programs for the Pacific Islander community throughout San Mateo County.

In 2009, she founded the Pacific Islander Community Partnership as a direct response to the growing decline of Pacific Islander student graduation rates, rising incarceration, and the need for advocacy that is culturally appropriate. With a mission to “Engage, Educate and Empower Our Pacific Communities,” the partnership continues to serve communities with a local, state, and global reach.

“I know my worth and value”

For those who question whether Liaiga-Anoa’i can speak for more than her Pacific Islander community, she replies, “I get the backlash of that, where people feel that it's not inclusive of everyone, [or say] that I'm running just to represent my community. I can understand the comments and where it comes from. My biggest thing is making sure people hear that I'm qualified to do this. I know my worth and my value. I know the importance of coming to the table with intention and humility, because there's no ‘I’ on the council. I don't make a decision as an ‘I’ because there has to be consensus.”

Liaiga-Anoa’i’s passion transcends racial and ethnic ties, she said. When she first ran for the school board, it was as a mother of a child with special needs. Liaiga-Anoa’i recognized that the school district wasn't meeting her youngest child and wanted to serve as a bridge.

A product of public school education herself, she has stood alongside other families and organized protests against multiple school districts to overturn policies and actions that negatively affected students of color.

As part of the school board, she realized that affordable housing was the biggest issue in recruiting and retaining educators and staff for her city. These days, she drives past the site where school district staff housing is being erected. “We're the only elementary school district that is building workforce housing in San Mateo County,” Liaiga-Anoa’i proudly exclaims. “It's amazing.”

With a deep commitment to equitable access to education, Liaiga-Anoa’i has also developed youth programs to create entrepreneurship opportunities and creative extracurriculars.

A self-described “youth development junkie,” Liaiga-Anoa’i saw that there was a lack of programming that supported entrepreneurial thinking and pathways into internships in San Mateo County, particularly in Daly City. Just a few weeks ago, Daly City agreed to build a youth employment program modeled after San Francisco’s Mayor's Youth Employment and Education Program (MYEEP).

One time, Liaiga-Anoa’i ran into the actor Edward James Olmos at a conference. Together, they talked about the need for a space for youth in the arts, particularly behind the camera as directors in order to create a pathway toward the entertainment industry. The youth cinema project Olmos proposed was taken up by Santa Clara County, but no other Bay Area school districts. Liaiga-Anoa’i jumped at the chance to bring the program to Daly City. That was four years ago; today the program in Daly City is flourishing.

“We get to go to our local movie theaters. And just recently, we saw our students' films on the big screen,” Liaiga-Anoa’i says. “The program is aligned with common core standards in their learning. So that was an ‘aha moment’ for me.”

Building civility and cohesion

What goals does Liaiga-Anoa’i have if elected to the Daly City City Council? The former liaison between Mayor Willie L. Brown and the Pacific Islander community says: “Work has stalled. Movements and initiatives that could have been handled differently on the council could have seen the light of day, but because there is tension, there are things that have not been productive.”

Mental health and how these interventions and wellness programs are implemented is also a huge concern, she said. “Women and girls continually do not prioritize themselves and many times neglect ensuring that they are in a good place—mentally, spiritually and physically,” she noted previously. “I have found in most recent years is that if I am healthy, I am able to be a more thoughtful contributor to important decisions that impact the work I believe in and belong to.”

She noted that addressing mental health requires going beyond that of cultural or ethnic acknowledgement, and instead fostering cultural competency or sensitivity.

That's also tied to housing and displacement, she added. “How are we doing in programming and engaging our populations in a dignified manner?” she asks. “I've heard multiple constituents in the community say, ‘I just won't go [to the community centers]. I'm not treated with respect.’”

She believes that it’s about revamping the systems, and making sure government entities ask how they’re connecting the dots to ensure they’re engaging their community with respect and keeping them in the loop about opportunities and resources they can access.

Liaiga-Anoa’i acknowledges that there won’t be a solution overnight. She emphasizes a desire to work with law enforcement and other government entities in order for them to transparently and honestly confront the explicit bias in their institutions, while also noting that her son has often been racially profiled in her own city.

“People feel uncomfortable about those conversations. They say, ‘Oh, we're doing it,’” she says, “but are you doing it with intention and accountability and transparency? We can't just do it, leave it alone and check the box and move on.” There has to be great intention, follow-up, and accountability with how they are implementing what has been learned, Liaiga-Anoa’i insists.

“I want to be the bridge,” she says. “I'm on the ground. I understand the needs. But the biggest component for me is being an avid listener and not telling people what they need, but allowing the space to be heard and being the vehicle to connect to resources and creating the space for conversation to meet solutions.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This story was originally published by Mochi Magazine, the longest-running digital publication for Asian American women. Follow @MochiMagOfficial on Instagram to get the latest in entertainment, books, and more all from an Asian American perspective.

About Mochi Magazine: Since 2008, Mochi Magazine has published content by our community, for our community from entertainment to activism to lifestyle, building on what it means to be Asian American bit by bit.