Between 6th and 7th Avenue in Delano, California, a slab of stone lies on the Earth. Surrounded by rows of gray headstones and blades of green-yellow grass, the stone lies face up to the heavens.

Unlike some of its neighbors, who find the protection of shade from towering trees, the stone is constantly exposed to the harsh California sun, and so it bears the physical signs of the weather it endures. Cracks, chips, discolored stains. White blotches on the stone mar the hands of an engraving of a shepherd Jesus cradling a baby lamb. “Beloved Husband and Father,” the gravestone reads. It does not read “Admired Labor Leader,” nor “Revolutionary Immigrant Rights Activist.”

Six feet under this marker lie the bones of Larry Itliong, a man who once bore the same treatment as his gravestone does now.

Patricia “Patty” Itliong Serda is the youngest daughter of Nellie and Larry Itliong. In Patty’s fondest memory of her father, she sits in his lap before bed, stroking the small emery board stick attached to one of his many, many collared shirts. He combs her hair, and young Patty relishes in the feeling until she falls asleep. This was their nightly routine until Larry passed away on Feb. 8, 1977. The gravestone reads right for Patty, to whom Larry will always be a beloved father indeed.

A current resident of Delano, Patty wishes she could thank him for the work he’s done, but losing him at seven years old meant that she didn’t yet understand much of the groundbreaking work he was doing until he was gone. All she knew was that she lost her father, and it hurt.

At times, Patty feels overwhelmed by the vision of farm workers out on the field sidelines. The mere existence of restrooms, shade, clean water, and water breaks. She drives past them and thinks, “If only my dad knew.”

If only her dad knew. If only he knew that the fruit of his labor would yield benefits and better treatment for all agriculture workers, the Filipino community included. If only he knew that his humble organization, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, would blossom into the United Farm Workers, one of the longest standing, most effective labor unions in the nation today. “If only he knew,” Patty thinks often, “he would be proud.”

Son, immigrant, father.

Born on Oct. 25, 1913, to Artemio and Francesca Itliong in San Nicolas, Pangasinan, Philippines, Larry grew up surrounded by family. His father, Artemio, was a farmer, and he instilled in Larry the idea that all people are created equal. Larry looked up to his father and his fellow farmers as kind, religious people—a supportive agricultural community.

At 15, Larry immigrated to the States as a part of the first wave of Filipinos on American soil. This first generation of Filipino immigrants are known fondly as the manongs, an Ilocano term for older brother. In America, Larry and the manongs would not be met by much support or community. Larry in particular would not be given opportunities to fulfill his dream of becoming an attorney. The manongs would not be met with welcoming arms to the American workforce, and soon they would realize that people like them, brown-skinned and wide-eyed, were not meant for the American Dream.

Even with this realization, Larry’s eyes never narrowed. Marking his brown face with sun and smile lines, less than a year into his residency within the States, Larry partook in his first agricultural strike. In 1930, he struck with a group of lettuce workers in Seattle, Washington. He then returned to Alaska, where he had previously been canning salmon, and organized with the Alaska Cannery Workers Union, the first labor union he was part of in the States.

According to popular legend, it was in Alaska that Larry earned the nickname “Seven Fingers” after losing three during a canning accident. According to Larry’s wife, Nellie Itliong, Larry lost the three fingers while jumping trains to travel in his adulthood.

Larry “Seven Fingers” Dulay Itliong left behind seven children in this world. Four boys, and three girls. While his accomplishments and roles as a union organizer and strike leader may not be as widely known or celebrated as those of his Mexican counterpart, Cesar Chavez, the impacts of Itliong’s work are long lasting indeed.

Farmer, canner, messman.

Including the Washington lettuce strike, about 380 different agricultural work stoppages occurred in 33 states nationwide between 1930 and 1948. The earlier strikes paved the way for the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. Congress passed the NLRA to protect both employers and employees, especially physical laborers in private sectors, but it left out a crucial group of workers: those, like Larry, in the agricultural industry. The law covers most workers in the private sector, but it does not cover government employees, agricultural laborers, independent contractors, and supervisors, with limited exceptions.

Larry worked in the canneries until 1939, ten years after his move to the United States. That year, he enlisted in the U.S. Army as a messman and served for the duration of World War II. Even after his years of service, Larry never shook the feeling that life in America was defined as the “white people against the brown people,” he said in a 1970 oral history interview. He felt the white people hated him and those who shared his brown skin. He felt they wanted others to turn against brown people like him. “It was so intense,” he said.

If only he knew. If only Larry knew that this feeling would linger, even after his work toward fair treatment and his time on this Earth was over. If only Larry knew that 47 years after his death, his daughter and his grandchildren would be living through a time of anti-Asian hate. “If my dad knew,” Patty says, “if he were alive, he’d be the first person to stand up.”

A librarian for an elementary school in the Delano school district, Patty loves being able to share her father’s story with the youth. She believes it is necessary and important to educate children, especially Asian children, about their ancestors’ paths, including that of her father. For years, Patty has worked to cultivate regard and respect for her father’s legacy. She refuses to let him be forgotten.

Leader.

In Stockton, 1948, 189 miles from his gravestone, and 46 years from its necessity, Larry’s brown skin bore the heat of the California sun. He and dozens of the manongs were scattered in a field with thousands of green, deceptively feathery-looking stalks. Daily from two in the morning to two, three, four in the afternoon, Larry and the manongs gave their backs to the sun, hinging to the ground to snap and harvest firm spears of asparagus. After cutting ten feet into the grove, Larry would look back at the stalks he had just left barren. Disbelief and fatigue would plague him every time; the asparagus seemed to have risen again.

Here, Larry and the manongs involved themselves in the first major agriculture strike after World War II. Asking for an increase in wages, the Stockton Asparagus Strike of 1948 set the precedent for Larry to continue his organizing and activism efforts after the war.

In 1956, Larry established the Filipino Farm Labor Union in Stockton. Within the next ten years, Larry moved to Delano, California.

“Delano brought me here,” he said in the 1970 interview, “I didn’t bring myself to Delano.”

The move brought change within his organizing efforts, and the Filipino Farm Labor Union evolved into the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee.

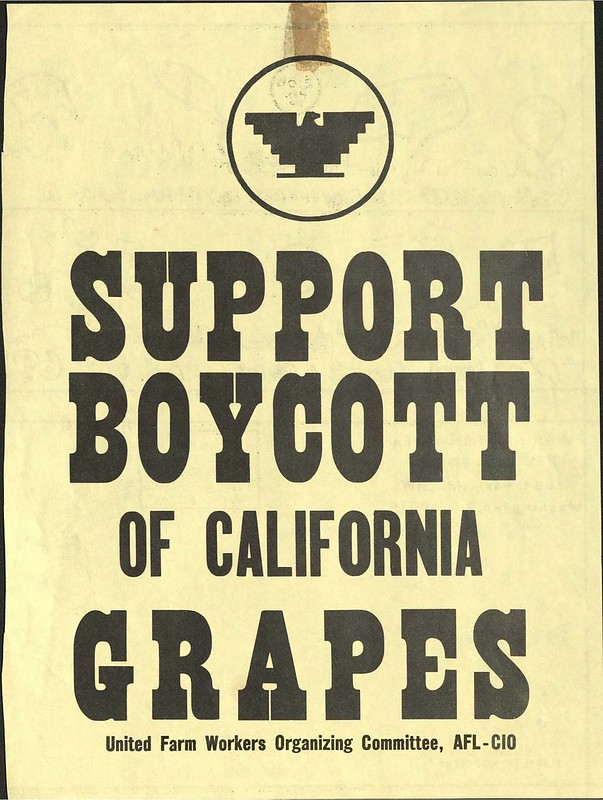

The first harvest of grapes in May 1965 for a grower in Coachella Valley gave Larry and the manongs yet another hot, exhaustive, underpaying assignment. The initial wage of $1.10 per hour did nothing to inspire their enthusiasm, so Larry proposed a strike. He led the manongs in a walkout that would ultimately inspire another strike, his largest, in September of that year. Larry called for an increase in pay to $1.45 per hour. Nine days later, the grower agreed to raise their pay to $1.40.

Organizer and activist.

The AWOC headquarters were located at “Filipino Hall,” 1457 Glenwood St., Delano, CA. Once, papers and notices were taped on the windows of the small cream building, and tacked to the interior walls. A notice containing an eight-step process to follow when a labor dispute arose and a picker called in for representation. Business cards for 24-hour bail bonds services. Reminders not to use the community telephone for long-distance calls, unless you had the permission of representative Walks or Arellano. Today, the hall’s exterior is accented with green lining and lettering that reads, “Filipino Community Cultural Center of Delano.”

While it was the home of many Filipino-dominated AWOC meetings, the hall is currently listed in the National Parks Service as a Cesar E. Chavez National Monument. The largest public high school in Delano is named Cesar Chavez High School; it is the school Patty’s daughter once attended. Despite Larry’s leadership role and obvious impact on the agricultural community, Delano has yet to honor him with a monument, school, or street. The Larry Itliong Library became the first tribute to him in 2021. The Larry Itliong Unity Park, which just opened this month, is now the second.

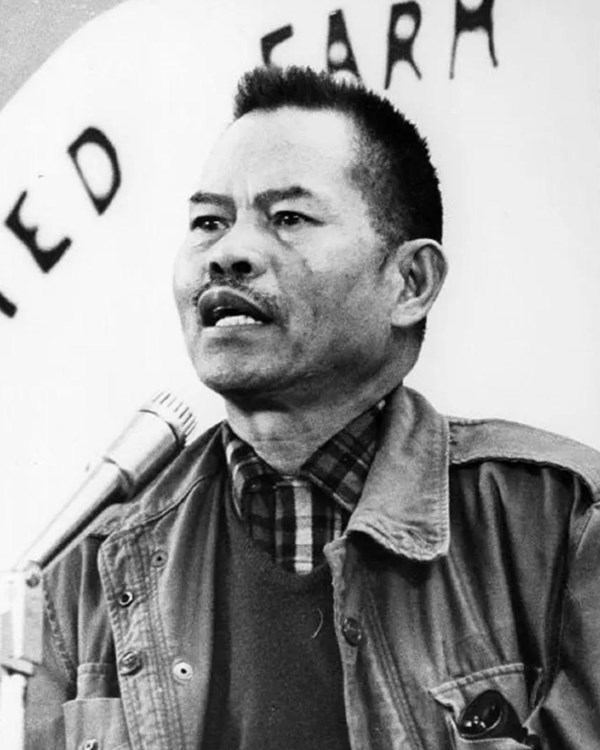

After years of enduring poor wages and working conditions, Larry gathered members of the AWOC in Filipino Hall on the evening of Sept. 7, 1965, to vote to go on strike. Sweating in the crowded space, the AWOC voted yes. They embarked on a work stoppage the very next day.

On Sept. 8, 1965, the legendary Delano Grape Strike officially began. Larry and the manongs started simple, with a sit-in. It was quieter than one might imagine a strike to be. No picketing, no chanting, simply sitting and occasionally chomping on a cigar. Larry felt a sense of anticipation. After the first three days or so, if he looked around at the faces sitting in with him, he might have noticed worry lines beginning to form on the faces of those who were losing precious income by striking. Income they needed to support and feed their families. Larry would have known the feeling. He believed in what was told by the old people, that if you get married, you had to be sure to support your wife and children. At least, that’s what his father told him.

A few days into the strike, when no action had been taken to end the sit-in, the growers began to move in strikebreakers—people hired to replace the strikers and render the work stoppage ineffectual. In response, Larry and the strikers established picket lines at the fields, packing houses, and cold storage plants. It wasn’t enough, and strikebreakers still got through.

Unifier.

Larry first met Cesar Chavez in 1960 during a meeting about farm labor.

His initial assessment of Chavez was not great. He met Chavez in the company of Filipinos whom he knew to be in shady operations, people who Larry thought were only interested in working for themselves, not the Filipino people.

“I said to myself, if he’s with a crowd like that, he’s going to advocate what is only good for him,” Larry said in the 1970 interview. So Larry walked away.

Five years later, Larry returned. He asked Chavez and the predominantly Mexican National Farm Workers Association to join the AWOC on their strike. Originally, Chavez was reluctant to join, until Larry convinced him that the NFWA needed to act as a union, rather than a community organization. He hoped the NFWA would share his interest in gaining proper living conditions, so the farm workers could work to live, not live to work.

In asking Chavez and the NFWA to join their efforts, Larry hoped to foster a sense of unity between the Filipinos and Mexicans—the two races dominant in the fields at the time. Larry thought the growers were constantly pitting the races against each other, especially in grape picking.

Agreeing with Larry’s vision for a more unified agriculture setting, Chavez and the NFWA officially joined the Delano grape strike on Sept. 16, 1965. The strike targeted approximately 33 grape growers combined, most notably the large growers DiGiorgio and Schenley.

Less than a year later, in August 1966, the two organizations made history and merged into the United Farm Workers labor union that is still around today.

Four years after the merger, 26 grape growers in 1970 signed a union accord promising better wages and better treatment of the agriculture workers. Five years after its onset, the Delano Grape Strike finally came to an end.

In 1971, Larry resigned from the UFW. He felt like the benefits were being disproportionately dispersed between Mexican and Filipino workers, and felt the need to leave the union entirely.

“There was also some tension there because a lot of the meetings were conducted in Spanish only. And a lot of Filipinos lost their seniority when they became part of the union,” author Gayle Romasanta said in an interview with The New York Times. “They’ve been there since the 1920s and 1930s, and when the U.F.W. came together, everyone was leveled.”

It seemed that the new organization of the UFW was recreating the exact racially charged division that they had worked so hard to destroy. It was as if the Filipino laborers were being forgotten amongst their own.

Forgotten, and remembered.

Patty’s work to ensure her father and the manongs has not gone unnoticed. On Larry Itliong Day, Oct. 25, 2021, her library was renamed after her father, marking it as the first official tribute to him in all of Delano. The Larry Itliong Library features a mural of Patty’s father on the library walls. His piercing gaze is now permanently set upon her efforts to uphold his legacy. Though a mural is no replacement for him, Patty is finally able to see her hero again, everyday.

More and more people have begun to recognize his achievements. Dr. Dawn Mabalon and Gayle Romasanta authored “Journey for Justice: The Life of Larry Itliong,” detailing Larry’s fight for farmworkers’ rights. This past March, it was adapted into “Larry the Musical,” a production that ran for a month in San Francisco. Notably, it has been Filipino scholars and artists that have brought these celebrations of Larry’s life to fruition. Even with the increased recognition of his accomplishments, there is still work to be done to bring his name out of the shadows.

Marking the beginning of AANHPI Heritage Month, Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus Chair Rep. Judy Chu (D-California) acknowledged in a press conference Larry’s contributions to this country.

He was “one of California’s greatest labor leaders,” Chu told The Yappie. “Larry’s unrelenting advocacy has had a profound impact on farm workers’ rights today, and we must always honor his legacy as one of the most important pioneers in American history.”

Patty, who has always worked to honor her father’s legacy, has just named a local park after him. On May 11 this year, the Larry Itliong Unity Park opened in Delano, a symbol of the unifying work her father dedicated his life to.

Finally, acknowledged.

If only he knew. If only he knew that feeling of being forgotten would lead to his name often being left out of history. If only he knew that his role and legacy, with many, many, other leaders of Asian descent, would be victim to erasure in American history. If only he knew that his work would pay off but he would never get any of the credit, would he do it again? Patty, his daughter who keeps his legacy alive by teaching it wherever she goes, says yes.

Patty knows firsthand the difference in public acknowledgment between Chavez and her dad, but it is neither one’s fault that Larry was for so long forgotten by history. She feels that any lingering resentment between the two was always overshadowed by their shared desire to heal and better the California immigrant-agriculture community. She recalls a eulogy Chavez gave at her father’s funeral, a final symbol of unity between the two labor leaders.

Her seven-year-old self couldn’t grasp the importance of Chavez speaking, but she reflects on the words she doesn’t remember. Oftentimes, when Patty stands above her father’s grave, she looks at the engraving of Jesus and his baby lamb and thinks of the short seven years she spent with her father. If only she knew.