A growing number of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander artists are incorporating into their works the climate issues affecting their homelands and the way they’re intertwined with their identities and cultural heritage. They shared with me how they use their art to help spark conversation.

The Pacific Islands: For centuries, military presence and nuclear testing by the United States, Spain, Japan, and other countries introduced a variety of diseases among Pacific Islander communities and significantly altered the environment. The U.S.’s military build-up since World War II has especially caused greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels and pollution leeches to infect the ground and water in over a dozen islands, including Wake Island and American Samoa. The environmental toxicity forced Pacific Islanders to emigrate from their homelands en masse or adapt and move away from their Indigenous ways of living.

- In the Marshall Islands, as reported by The Yappie’s Javan Santos and Joshua Yang, nuclear radiation exposure caused by U.S. forces’ nuclear bomb testing between 1946 and 1958 increased risks of health problems and death. Increased flooding, contaminated food supplies, and other environmental issues were only worsened by climate change.

- In Guam, the American government’s ongoing military activities have resulted in similar environmental contamination and desecration of culturally significant sites. The United Nations has in recent years communicated concerns about possible human rights violations to the federal government after facing pressure from Chamorros and human rights groups.

- Other Pacific Islands and nations that have contended with the same threats are now looking to implement mitigation and adaptation solutions by reclaiming their Indigenous knowledge in tandem with new renewable energy technologies.

Hawai‘i: After white Americans overthrew the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 and illegally annexed the islands in 1898, colonizers cleared out native forests for sugar plantations and exploited water resources to the point of drying out streams. The development of the sugar cash crop economy and increased tourism further resulted in water, land, and cultural damage.

- While the majority of Native Hawaiians reside in Hawai‘i, as of 2022 NHPIs make up 10% of Hawai‘i’s population—a steep decline from the start of the 20th century, when they comprised 30.5% of Hawai‘i’s overall population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

- Tourism today makes up roughly a quarter of Hawai‘i’s economy but continues to use up a large percentage of the islands’ resources. “21.7% of the Big Island of Hawaii’s total energy consumption, 44.7% of its water consumption, and 10.7% of its waste generation,” a report from nonprofit The Kohala Center noted in 2015.

- Between 2021 and 2022, waste leakage from nearby U.S. military bases further contaminated waters, leading to protests over the huge health concerns it posed and officials’ slow response. Last year, the Navy released over 1,000 gallons of raw sewage into Pearl Harbor near Honolulu.

Native Hawaiian sculpture and installation artist Kaili Chun, based in Hawai‘i, engages with ideas of physical space, natural environment, history of land, and culture through her sculptures and installations.

- “As a Native Hawaiian, we have experienced colonization, capitalism, democratization in the service of others rather than in the service of ourselves,” Chun said. “My art reflects that history … As our population declines, we need to maintain connection to the culture and that means connection to this land.” Chun calls it “ʻāina,” a term that includes the ocean and “all the resources around us.”

- Space is a particularly important element in her work, a reflection of the way the Native Hawaiian community has diminished over the years. “With my installations, I really choose to occupy space,” she said. “Somehow in some way, whether it is literally gallery space or air space like within an atrium … But I feel it’s important to claim space, physical space, so that I can exist in it and share some of the history and genealogy of that land and culture and place.”

- In her piece “Muliwai,” she explains “that’s where the freshwater meets the ocean. And it's in a portion of Waikiki that's very touristic and I think that it is pretty enough so that people will gravitate to explore it a little bit. That attractiveness, I think, is what I hope to lure people in and ask questions.”

- “I want to create spaces for conversation between people so that we can have a more meaningful discussion of each of our perspectives in a safe way, safe place without being too contentious,” she added.

- She also pointed out how Indigenous ways of living have been altered by the need to adapt to urbanization and tourism for their economy, which was a focal point in “Muliwai.”

- “All of our urban spaces are conditioned,” she said. “Do we really need that as a part of our lives or are there ways for us to incorporate the natural trade winds that we should be taking advantage of and that we always have been taking advantage of? These are questions we really need to ask ourselves.”

Abigail Romanchak is another Native Hawaiian artist who centers her art on Hawai‘i and its natural environment. “I care so deeply about the land and its people,” she said in an email interview. “I am acutely aware of the rapidly changing landscape of my birthplace, Maui … My brothers and I spent most of our time outdoors exploring and observing Makena's rugged coastline. I think this childhood and lifestyle definitely influenced my connection to a sense of place.”

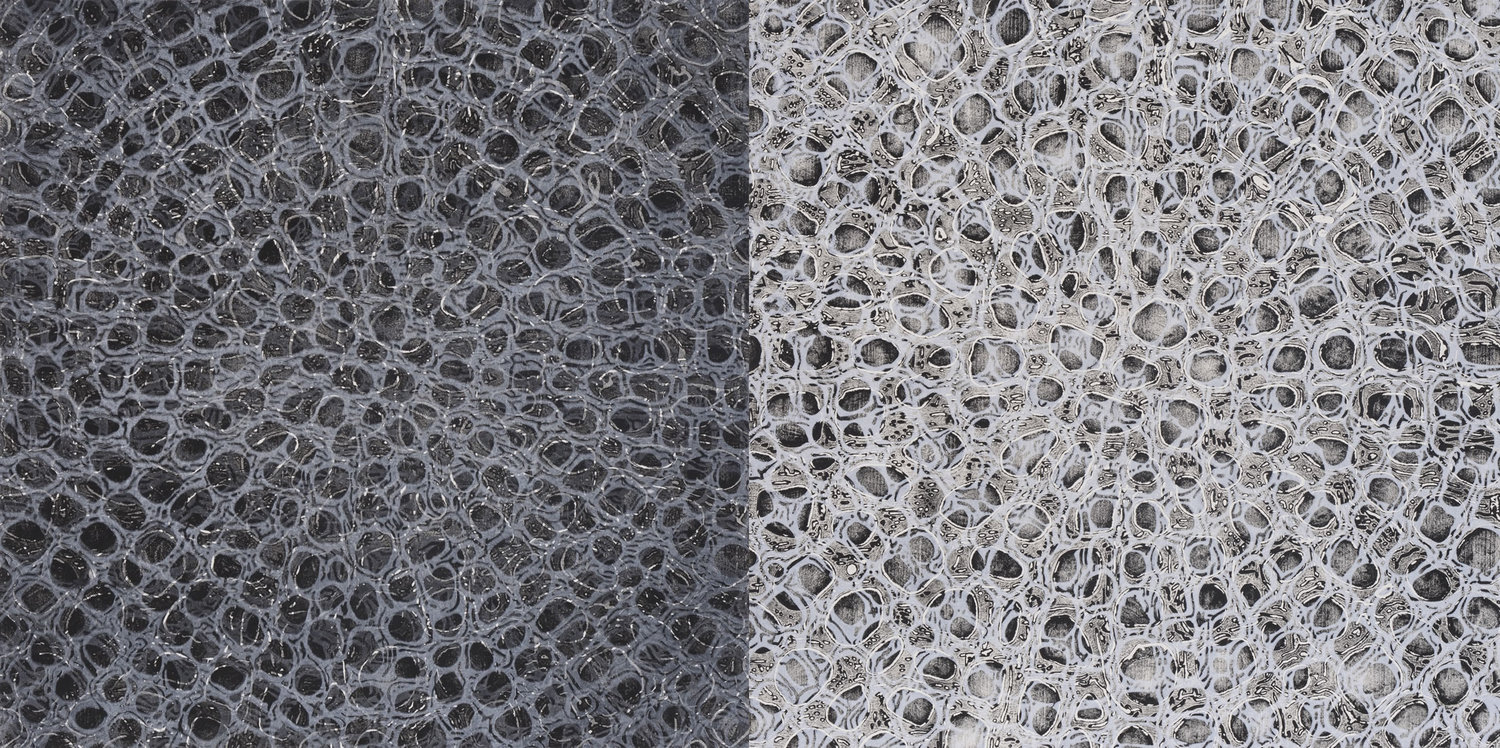

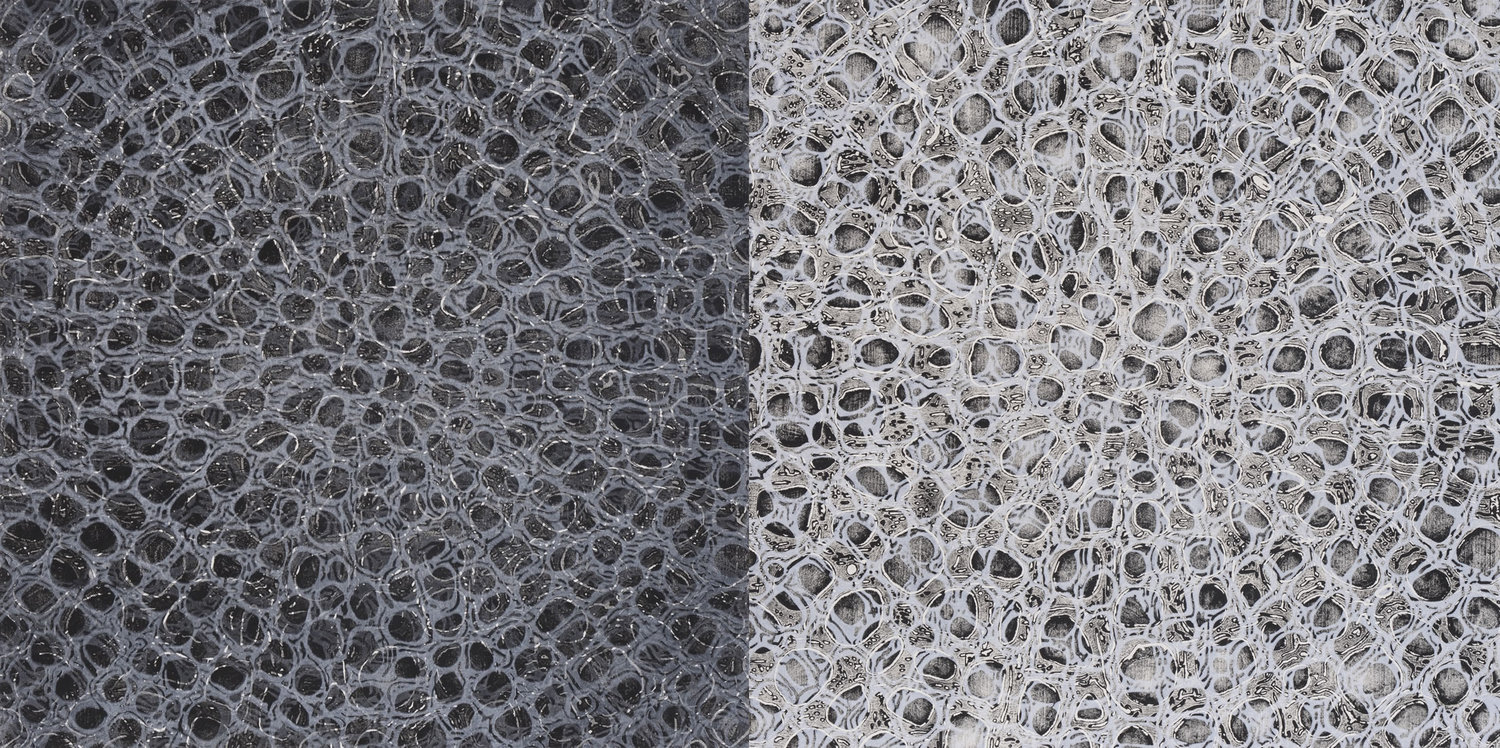

- In 2018, she was asked to participate in a group show in Germany with several other Kanaka Maoli artists. The theme of the exhibit was “Aloha 'Aina,” which she chose to express by highlighting “the health of our marine ecosystems and us[ing] the image of the interconnected structure of a diatom to create a series of layered woodblock prints.”

- The finished piece, titled “He Ho'ike No Ke Ola,” focuses on “the relationship between micro and macro scenarios,” Romanchak shared. “Marine food chains collapse when diatoms, microscopic indicators of health and wellbeing in ocean ecosystems, are unable to thrive. This causes irreparable damage to reefs and other habitats upon which land and water systems rely, making islands vulnerable, and in some cases, uninhabitable.”

- “The complex networks of the requisite diatom give reason to ponder far-reaching ramifications of unsustainable practices,” she added. “These microscopic maps of wellness or destruction in our Hawaiian ocean waters have many parallels to the lives of Native Hawaiians.”

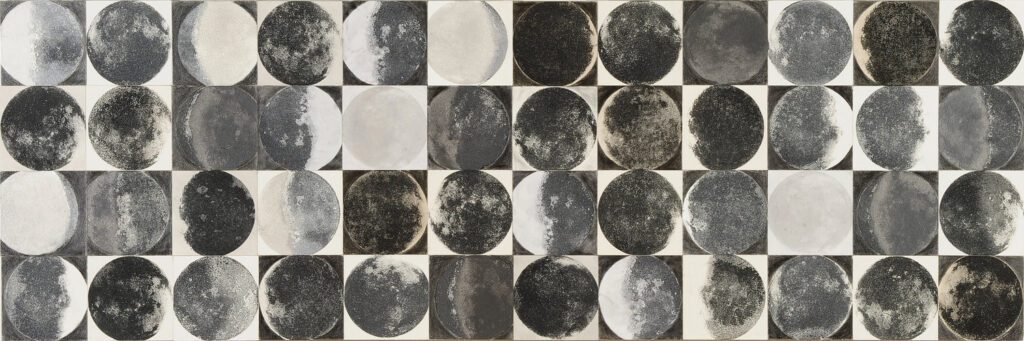

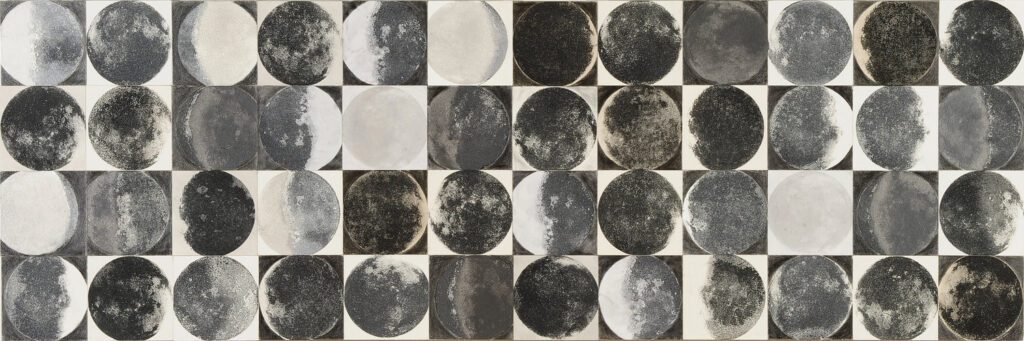

- For another group exhibition in 2008, she created a piece about the Hawaiian moon phase, when the moon is “waxing and nearly full,” after reading the epic tale about the Hawaiian goddess Hi'iakaikapoliopele.

- The night of the Hua moon phase “is considered sacred to the Hawaiian god of agriculture and as such is good luck for planting, fishing, and healing,” she wrote.

Graphic designer, graffiti artist, and mural artist Jason Pereira similarly incorporates much of his Samoan heritage and experiences into his artwork. Periera, a resident artist at the Pacific Islander Ethnic Art Museum and Constellations Fellow at The Center for Cultural Power, cites his hometown Leona in American Samoa and his family—especially his father, an architect—as influences on his work.

- He spoke to me about how murals are “public works of art” that need to connect with the community where they’re displayed. “They need to be part of that story,” Pereira explained. “The neighborhood is the one that’s going to live with this piece.”

- In 2018, locals selected his piece “Tautua Mural” for an installation in Long Beach at the Rear Wall of American Oil Gas Station. The mural shows a woman with a traditional headdress and Samoan tattoo performing a Samoan cultural tradition—the ava ceremony, which is held to formally welcome guests to the village. Next to the woman are the words: “O le ala i le pule, o le tautua.” It translates to: “The path to leadership is through service.”

- “This is a foundational principle of Samoan culture that I wanted to share with the community of North Long Beach through this mural,” he wrote on Instagram, referring to the neighborhood’s diversity. “With this piece, I also wanted to give a voice and a sense of honor to the Samoan community here … They've immigrated here from American Samoa & (Western) Samoa, via military service, farming, spiritual purposes, education, or just seeking a better life for their families.”

- “Throughout their time here, cultural teachings such as this Tautua proverb continue to be passed to the next generation as they have been in the islands through the centuries,” he said.

- The process of painting the mural involved his friends and family, as well as various local graffiti artists and taggers who helped ensure that it remained safe from vandalism. The mural program that spawned his creation began because a lot of walls were getting tagged, especially the one he eventually painted.

- Since 2018, it has stayed untouched. For Pereira, it is “proof of the power of community” when building relationships with the people “you’re putting your heart in.”

Below is a list of other NHPI artists who focus their work on their cultures and the natural environment.