EDITOR'S NOTE

Welcome to the tenth installment of The Yappie’s series featuring Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) newsmakers, rising candidates, and lawmakers.

Annie Wu Henry is on the phone with me as she makes the three-hour drive from D.C. to Philadelphia. She’ll be in Philly for two-and-a-half days before making the trek back down to D.C. on Wednesday and New York City Thursday.

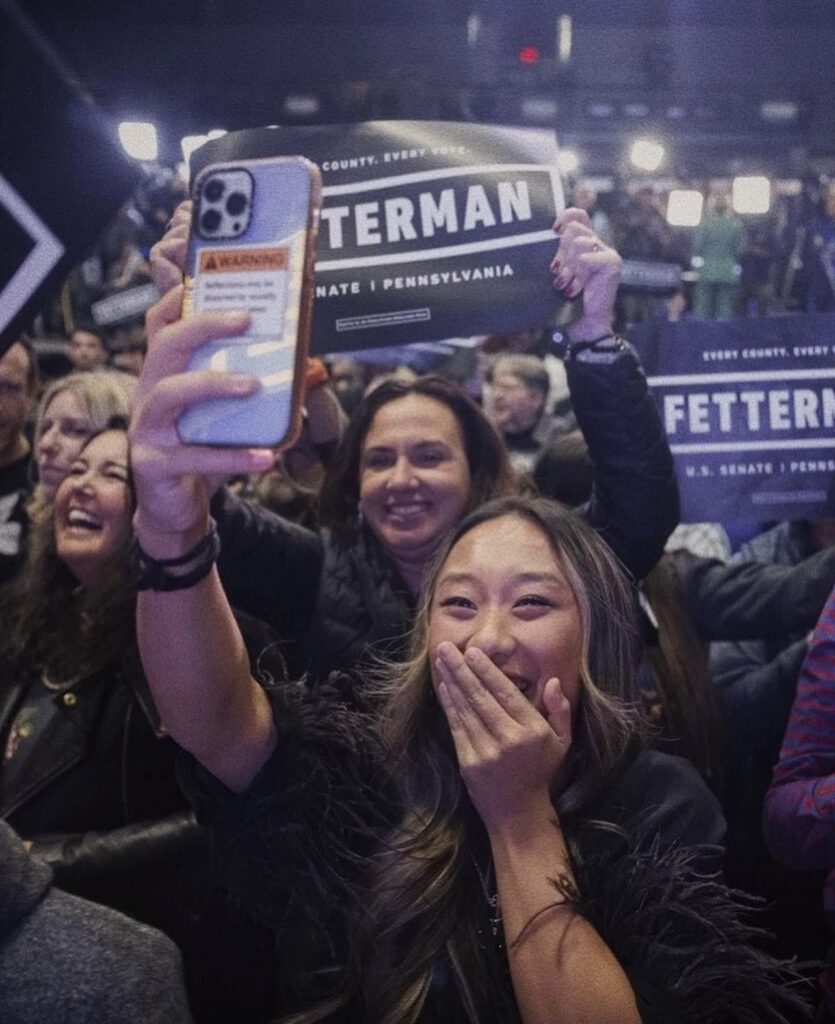

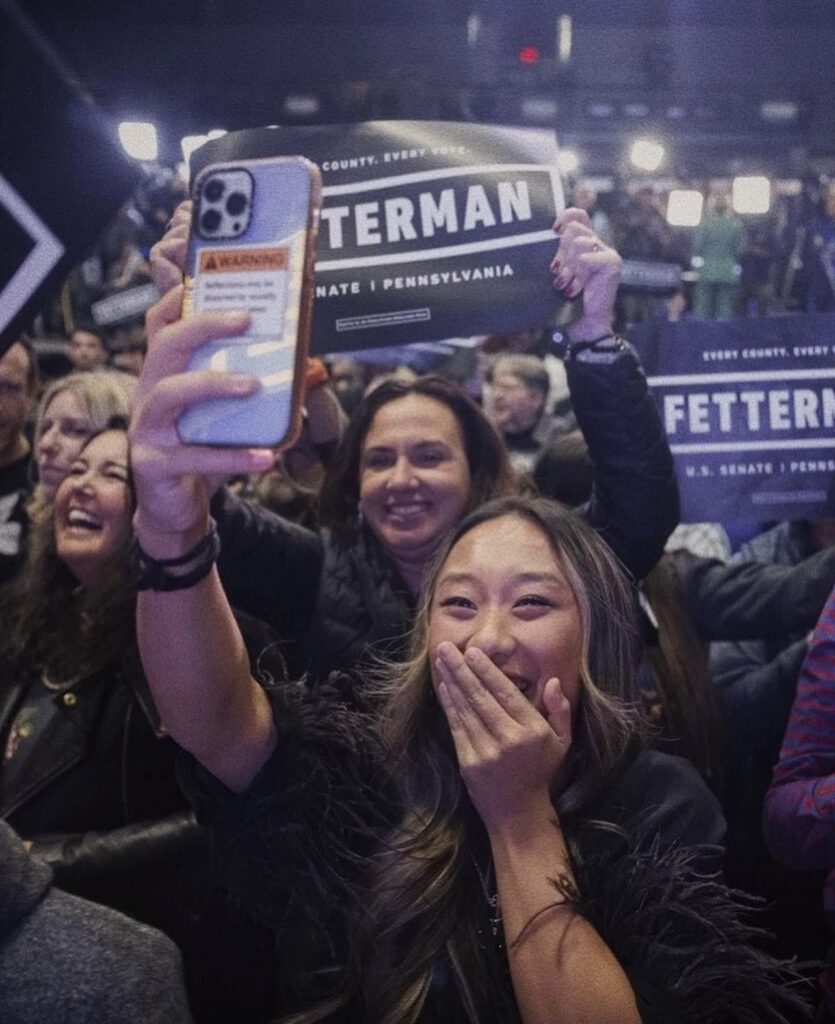

For Henry, it's the norm. People know her as John Fetterman’s TikTok whisperer, as one New York Times profile nicknamed her. After she helped get him elected to the U.S. Senate, she took some time to figure out what she wanted to do next.

Now, AAPI Victory Fund has announced that Henry has joined the political action committee as its new creative director. The position involves working closely with community groups to create content, manage campaigns, boost voter engagement, and highlight the PAC’s endorsed candidates.

With Henry at the helm, AAPI Victory Fund is rebranding its image as part of a larger bid to better reach voters, especially younger ones and those who consider politics inaccessible or too in the weeds.

Henry’s record of work involves campaign strategy and communications both online and off, but one of the most impressive achievements she pulled off came during the 2022 election cycle via TikTok, where she grew an account that topped 241,000 followers and regularly published videos that totaled over 3.5 million likes.

Afterward, she found herself at the center of national attention with newfound interest in how she helped Fetterman win his election using a social media strategy previously untried in politics.

“That magnitude of exposure that people can have—it’s not normal,” Henry tells me about the notoriety she suddenly attained. “I tried to stay grounded.”

Revitalizing the PAC

In recent years, AAPI Victory Fund—one of the largest political action committees focused on AAPIs—has taken on new significance with high-profile events featuring Vice President Kamala Harris, Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-Illinois), and Rep. Andy Kim (D-New Jersey), to name a few.

AAPI Victory Fund CEO and President Brad Jenkins, who first met Henry at a conference hosted by a Gen Z-focused organization, said her portfolio of work reflects “some of the most innovative political content that I’ve seen in a very long time.”

“There’s a trajectory of Asian American power and representation and excitement that’s happening in a lot of different areas, and she’s the perfect person to help AAPI Victory Fund tap into it in this moment,” Jenkins added.

Henry took a bit of a break after Fetterman’s campaign ended in November, recognizing the dangers of burnout in a “grueling” industry. “I wanted to be really intentional … and not just jump into something,” she says.

“But we’re doing a refresh with branding, with how we’re gonna look and feel,” she adds about her plans for AAPI Victory Fund. “It's not all just going to be endorsements and political statements anymore.”

That will look like highlighting the things elected officials and community members are doing, according to Henry. She wants the organization to be the place people turn to when they want to know more about the AAPI community in politics and its voting power.

“I think that there’s a lot of skepticism and a feeling of, you know, a lack of belonging or a lack of power,” Jenkins said. It has served as an obstacle to voter engagement among young Asian Americans, according to polling by RUN AAPI.

Henry is uniquely poised in her ability to counter that—what Jenkins calls “leveling up.”

Coming into her identity

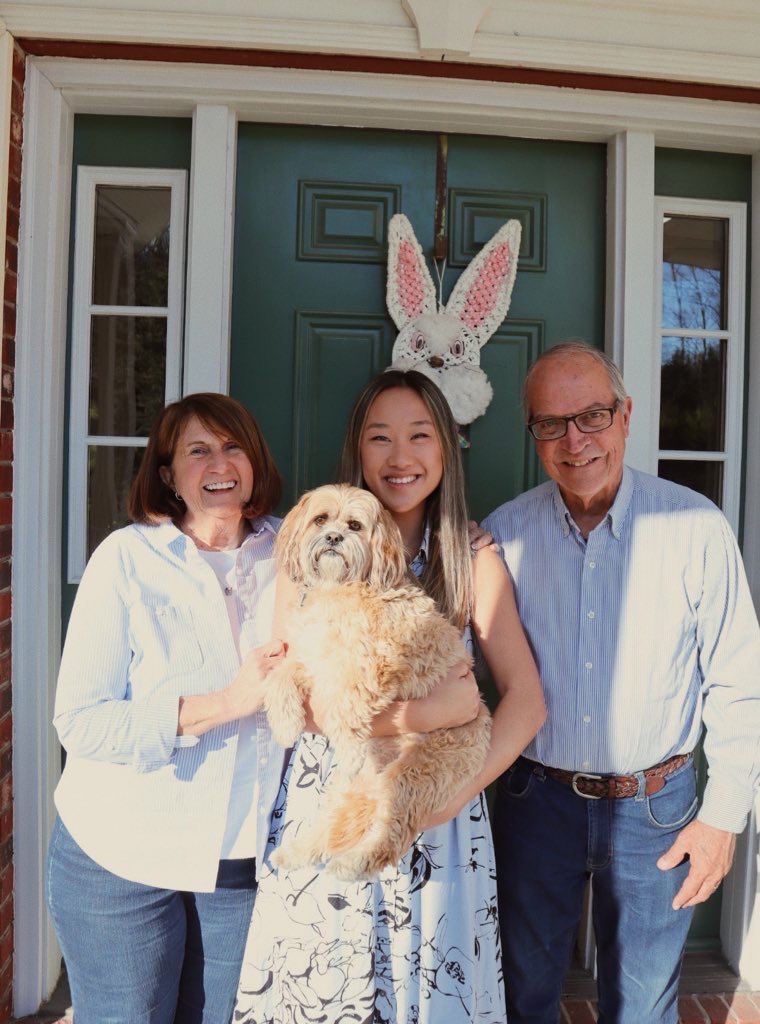

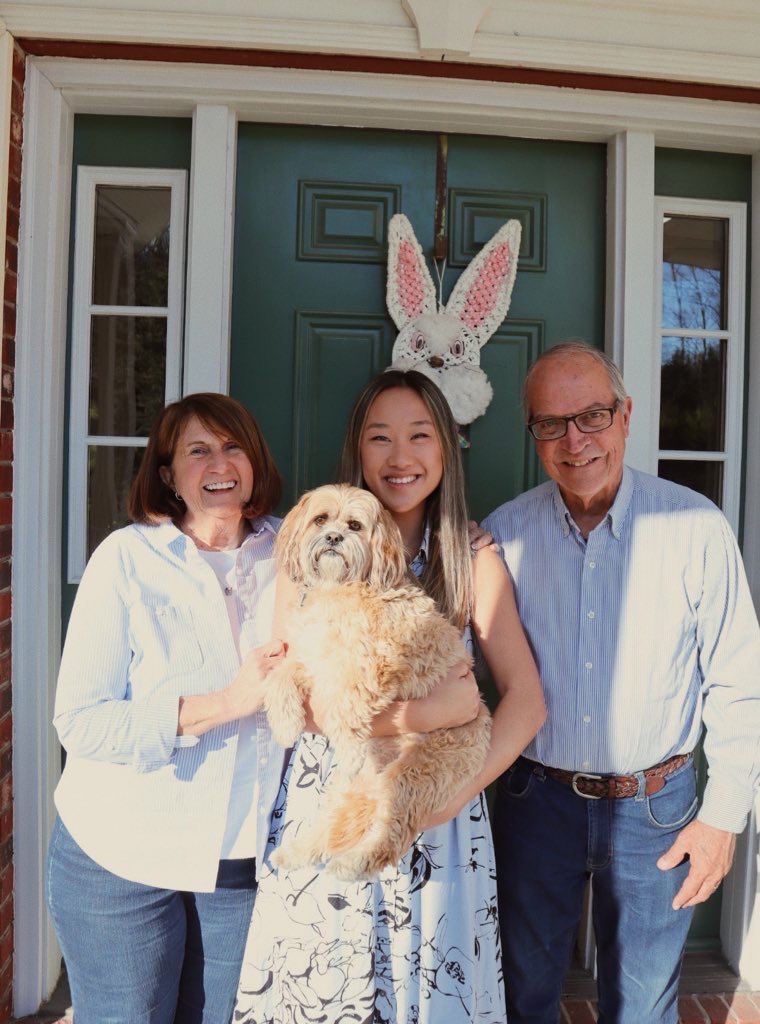

Henry grew up in a small, conservative town in Pennsylvania. Her parents, an older white couple who adopted her from China when she was 13 months old, “didn’t ever hide that I was adopted or that I was Chinese.”

Her family was part of a group of families with adoptees from China who would get together for events like Lunar New Year to foster a sense of community.

Though there were some microaggressions and other acts of racism targeting her in her hometown, she didn’t fully register what it meant to be Asian until she was a freshman in college when at a grocery store, Henry says, someone told her to go back to where she came from.

“I was just there returning my cart in this parking lot, and I wasn’t talking to them,” she says. “And just like, defeat. That feeling for the first time—you don’t know anything about me.”

Her awareness of her status as a perpetual foreigner intensified as she watched the country elect Donald Trump as president and moved to the South for her sophomore year of college.

And when COVID-19 descended and anti-Asian hate incidents started to surge in 2020, she felt an acute sense of paranoia and fear that followed her everywhere.

“I was wearing a mask,” she says. “People didn’t know that I had two white parents. People didn’t know that I only speak English, that I ate meat and potatoes growing up. People didn’t know all these things that I for so much of my life I think grasped as kind of that shared privilege.”

But none of that mattered, she notes, because she was ultimately “an Asian person wearing a mask in a supermarket.”

Her path to politics

One of Henry’s childhood memories is listening to the clean version of “Dear Mr. President” on her iPod as a nine-year-old girl. Though neither of her parents was very politically active, she started her college years as a government major, intent on learning about how it worked and how it didn’t.

She quickly realized that she would not enjoy working in the field, she said, finding it frustrating and slow on many accounts.

Later, she pivoted to a journalism degree with minors in political science, sociology, and anthropology after deciding that storytelling and connecting with other people is “what makes the world go round.”

Her thesis at Lehigh University focused on the concept of identity and how it interacts with our online personas and vice versa.

“Articles or podcasts or retweets or whatever, all those things come and go. I don’t want any of that to be just who I am. I want to be in the work because it’s important, and I want to keep doing the work because it’s important.”

—Annie Wu Henry

After starting her career in grassroots community organizing, she found her way to the national stage as a social media producer for Fetterman’s campaign. She often had to break down her vision to colleagues who didn’t understand online platforms in the same way. A lot of it relied on timing and the personality she wanted to convey, something that’s not always explicable.

“A lot of it I would start out and I would have to create seemingly something out of nothing,” she tells me. “We didn't have a template to follow.”

Say, for example, a five to 15 seconds-long video. It might look effortless and easy, but it takes “a lot of scrolling and a lot of brainstorming on how to put these elements together,” she notes. (She adds that she hopes it looks effortless and easy though—“that's the point.”)

These kinds of online tools aren’t going away anytime soon, and Henry echoes a chorus of voices calling on campaigns to better utilize social media to reach a wider array of voters.

“These spaces are just gonna continue to grow in how much they're being used, and what they're being used for,” she points out. “And so we need to continue to make sure that we are growing with that.”

The future

In addition to her new role with AAPI Victory Fund, Henry is also working with the Working Families Party and Philadelphia mayoral candidate Helen Gym (D) to provide support in voter outreach and strategy.

It’s a coming home of sorts for Henry. The D.C. world of politics isn’t always accessible—there isn’t really a playbook, especially for people of color from lower-income backgrounds. Putting down roots in Philadelphia, in her home state, allowed her to be authentic to herself.

“I have kind of this nice puzzle piece together, a set of work that I’m doing right now and I’m really happy and fulfilled with it,” she tells me as she continues her road trip. “It was a happy medium to be able to stay involved and engaged and support the Working Families Party, which aligns a lot with my values, and their slate of endorsed candidates, which includes Helen.”

“Everything kind of fits together really nicely, which is also why May is so crazy,” she laughs, referring to AAPI Heritage Month.

That doesn’t mean she plans to sit out of the 2024 cycle entirely, however.

“There might come a time that I do feel like my skills could be utilized in that cycle somewhere and I wanted to have the flexibility to be able to jump in, whether that’s in June or in September or January of next year,” she says.